Breaking The Ballet Body Taboo

The notorious ideals of the ballet world are everywhere you go, and there is an unhealthy standard of a skeletal figure that encapsulates its culture.

Social media proclaims that “every body is a ballet body,” and that ballet should be entirely enthralling; a dynamic approach to self-expression. Offline, we are told to diet.

“Lose weight, don’t eat that, suck in your stomach, count your calories.” It’s an endless spiral of negativity that conveys one jarring message to dancers: you are not accepted for who you are.

“She’s not one of the skinny girls,” a manager of a leading ballet retail store commented on my weight a couple of years ago after taking my measurements.

At thirteen years old, I didn’t quite know how to interpret this comment. Did it mean that my dancing ability would be forever lost due to my deemed unworthy weight? All I wanted was to purchase a new tutu. Instead, I began to question myself.

It wasn’t until later when I realized that I am more than a number on a scale or a view of another. I am a dancer, and that is what I simply want to do: dance.

Unfortunately, to be in the dance world is to endure criticism.

The notorious ideals of the ballet world are everywhere you go, and there is an unhealthy standard of a skeletal figure that encapsulates its culture.

I have found that body image is a surprisingly secretive topic among dancers. Everyone wonders and forms their own assumptions, but few dare to discuss it publicly.

I too spent most of my time as a dancer being embarrassed of the association with this seemingly superficial matter. However, as my training progressed and I began encountering the realities of the ballet world, the importance of speaking up became increasingly apparent.

As an optimist, I like to focus on the positive, and there are, in fact, many positive aspects of ballet.

Ballet should be simple. At its core, it is an enjoyable, expressive art form which is best supported by healthy training and fueled by a passion for dance.

Luckily, I have found support in my current ballet school. My teachers encourage healthy habits as well as a positive mindset regarding body image, and I truly appreciate that they want what is best for their dancers. Yet, I cannot escape the issues pervading the broader ballet community.

The year 2020 was an especially eye-opening period. Global lockdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic forced many dancers to step back, reflect on and share their experiences. Taboos were finally broken.

Kozhemiakin performs an arabesque at the barre during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Kozhemiakin performs an arabesque at the barre during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In a report by Pointe Magazine, Kathryn Morgan, a dancer who recently left the acclaimed Miami City Ballet after just one season recalled the day that she had lost her role in the ballet Firebird due to her weight.

"I was told that I wouldn't represent the company well, that I would be an embarrassment. I was a size 2. It was devastating."

Morgan, an inspiration to many aspiring dancers across the globe, has amassed over 230,000 followers by sharing her experiences in the industry as well as advice on her YouTube, educating dancers and non-dancers alike.

In a video responding to the emotional abuse at Miami City Ballet, Morgan reminded her followers, “You are a human being, not a human dancing.”

Social media has been vital to this uptick of shared experiences, both positive and negative.

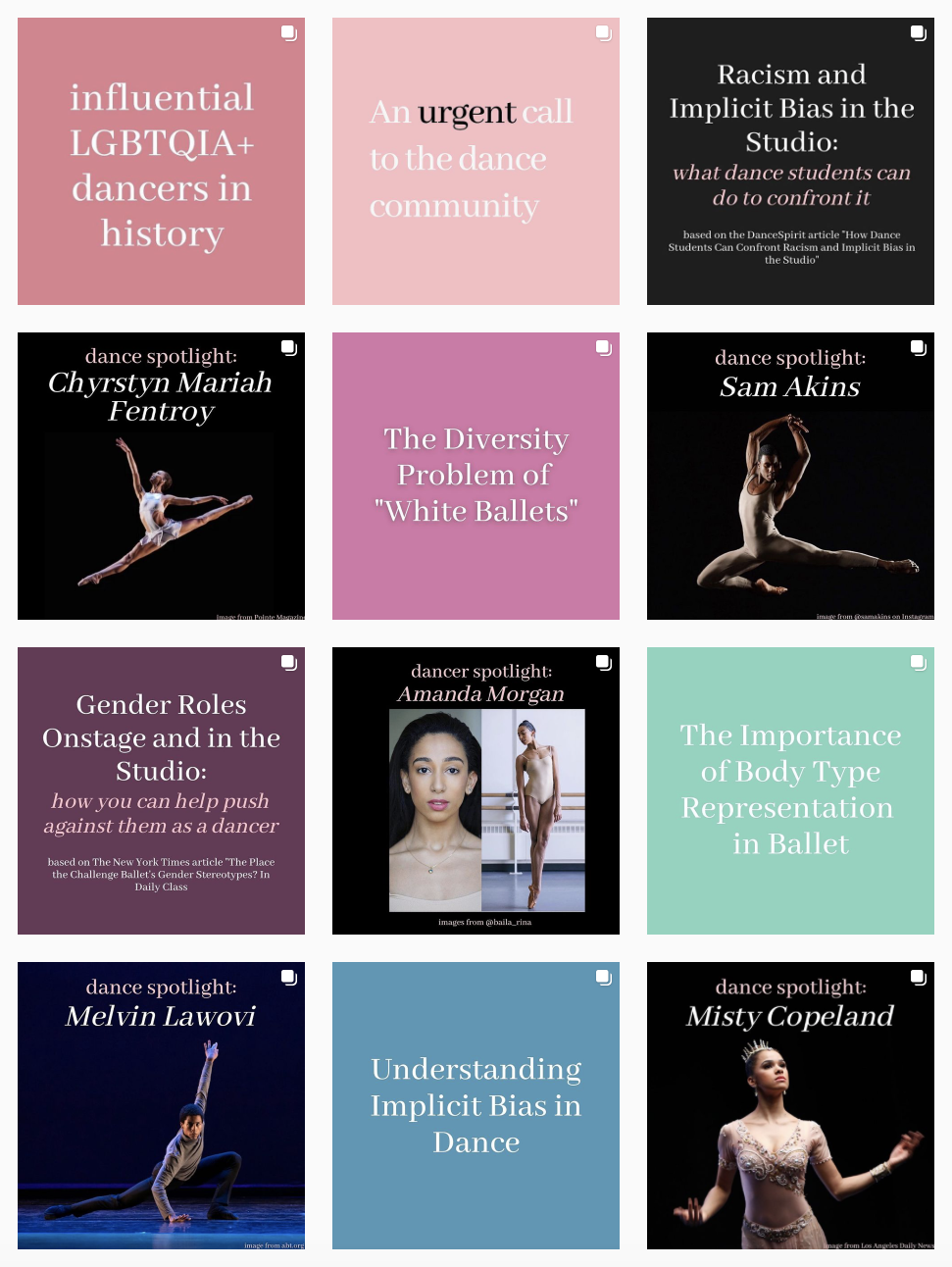

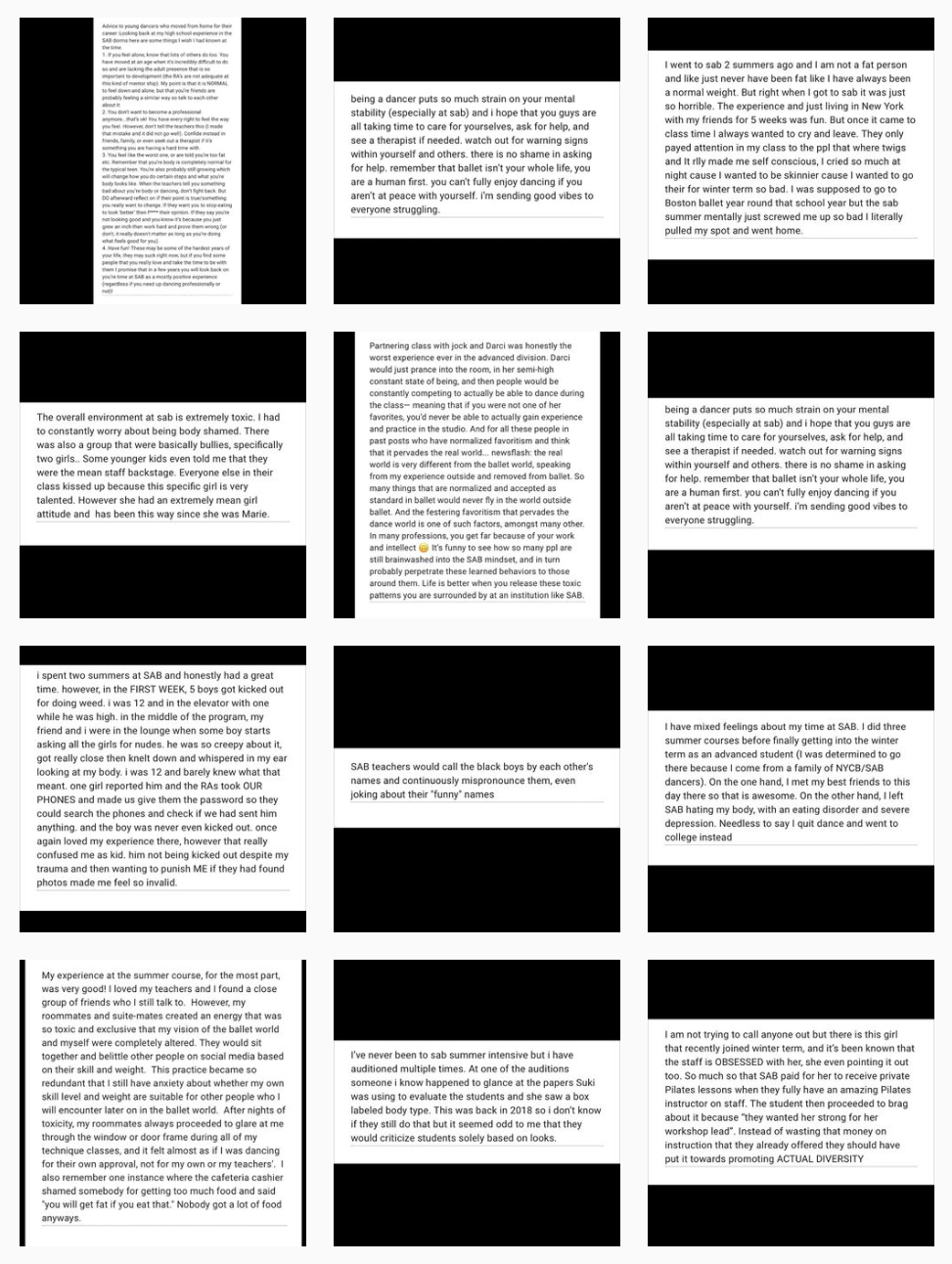

On Instagram, accounts designed to expose the deep-rooted toxic behaviors of leading ballet companies have skyrocketed in popularity. “Pointe for Progress,” a newly established Instagram account, sheds light on a broad scope of topics ranging from the importance of body type representation in ballet, to racism and implicit bias in the studio. Other accounts allow students who have trained at specific schools to anonymously submit stories of their experiences at that institution, resulting in a viral following.

Here are just a few quotes that encapsulate the judgemental nature of ballet.

- They asked me to lose weight and called me a ‘giant.’ It caused me to battle an eating disorder for years.

- At one of the auditions, someone I know happened to glance at the papers [the teacher] was using to evaluate students and she saw a box labeled body type.

- The overall environment at [the school] is extremely toxic. I had to constantly worry about being body shamed.

Additionally, many schools—mostly European and traditionally conducted in Russian (Vaganova) training —have weight charts that students are obligated to follow by contract in order to obtain their standing at the institution.

These charts, exemplifying the outdated beliefs often espoused by elderly directors of major ballet companies who establish the direction of the dance world, are capable of having severe mental repercussions on dancers.

Pointe for Progress, which is "a platform to amplify unheard voices in the ballet community. We want to spread awareness and promote personal research and advocacy," according to their Instagram page.

Pointe for Progress, which is "a platform to amplify unheard voices in the ballet community. We want to spread awareness and promote personal research and advocacy," according to their Instagram page.

Exposing SAB, an Instagram account where dancers of the School of American Ballet may anonymously submit stories about toxic experiences at the School.

Exposing SAB, an Instagram account where dancers of the School of American Ballet may anonymously submit stories about toxic experiences at the School.

A height/weight requirement chart from the Vaganova Ballet Academy website.

A height/weight requirement chart from the Vaganova Ballet Academy website.

Body dysmorphia among dancers is rampant, and The Washington Post claims that “one out of two dancers suffer from an eating disorder.”

In the article, Linda Hamilton, a psychologist who works with ballerinas affected by eating disorders, addresses toxic policies in dance institutions.

“Most ballet schools have incorporated nutritionists and other programs to help dancers stay healthy, but often you get mixed messages… The companies and schools may talk about health, then you see that the skinniest dancers are the ones who are getting cast in lead roles,” Hamilton said.

Now, in my third year at a pre-professional ballet program, I have finally learned to let go of the degrading comments and criticism of others, whenever they may occur. Instead, I feel grounded by my ability to control the outcomes of my own training.

Kozhemiakin with fellow dancers at the Integrarte Pre-Pro Ballet program. Photo courtesy of Integrarte USA.

Kozhemiakin with fellow dancers at the Integrarte Pre-Pro Ballet program. Photo courtesy of Integrarte USA.

Above all, I learned that you define your own happiness.

Before anything else — dancer, student, friend — you are human. Why relinquish your own happiness to please the physical preference of another?

Although it is distressing to face at first, when the negative aspects of the culture begin to outweigh the pure joy of dance and your own wellbeing starts to deteriorate, dance may not be the most healthy path for you.

Learning to love and prioritize yourself is a process.

It is the moment when you learn to unapologetically savor each meal, understand that appearance is subjective and find a supportive community, that you truly begin to recognize your worth as a dancer and a human being.