It's the People Who Matter

Thirty years after he first set foot on campus as a fourth grader in 1993, David Cutler ’02 still feels a deep sense of wonder and gratitude. Over the past decade, he has been privileged to work alongside many of his former teachers, who have now become his valued colleagues.

David Cutler's 4th grade class photo.

David Cutler's 4th grade class photo.

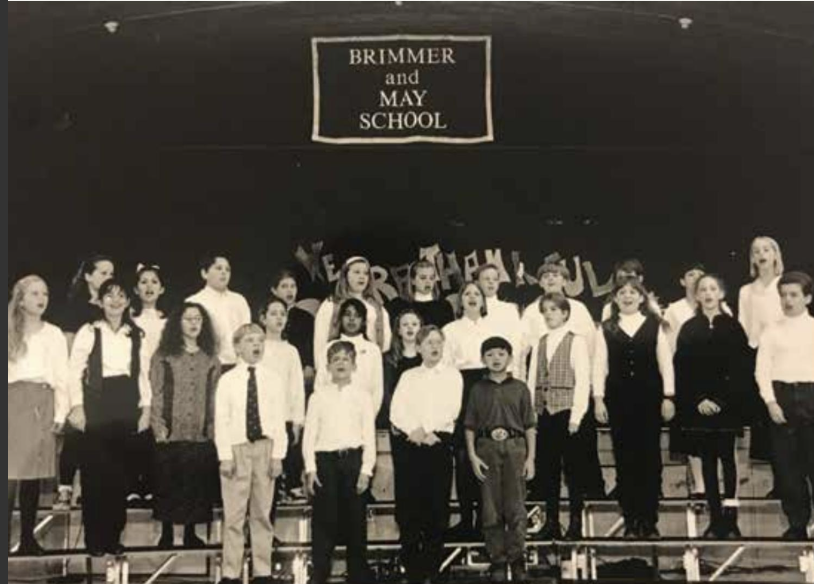

David Cutler, positioned in the front row and second from the left, performs a song with the May Choral during the commencement of end-of-the-year ceremonies. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School

David Cutler, positioned in the front row and second from the left, performs a song with the May Choral during the commencement of end-of-the-year ceremonies. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School

Sharin Russell chats with former Upper School Head Carolyn McKee during Green and White Games in 2001. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Sharin Russell chats with former Upper School Head Carolyn McKee during Green and White Games in 2001. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Sharin Russell, early in her career, having fun with her 4th grade students. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Sharin Russell, early in her career, having fun with her 4th grade students. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

In the School’s 2002 yearbook, my fellow seniors designated me as “Most Likely to Return to Brimmer and May as a History Teacher.”

Their prediction was no frivolous guess; they confidently anticipated that outcome (spoiler alert: they were right). Amid the uncertainties of our collective unwritten futures, at least that much stood certain. My classmates anticipated not only the compelling attraction that would draw me back, but also the transformative spark it would ignite within me—an unwavering commitment to pay it forward, sharing the knowledge, wisdom, and purpose that a fantastically talented group of educators had so graciously bestowed upon me. My teachers recognized my unique talents, addressing my needs with guidance and heartfelt support. Their impact continues to resonate, filling my heart with gratitude.

When I returned to Brimmer as an educator in 2014, after spending six years teaching at an independent school in Miami, Florida, I basked in the tender warmth of homecoming. Now, I aspire to inspire and empower students, drawing upon the influence of my past teachers—many of whom became colleagues—during my cherished years in this exceptional community. To fully grasp the deep significance my alma mater holds for me and understand how my time as a student here has shaped me, we must embark on a journey back in time.

Sharin Russell during her early years at the School as a 4th grade homeroom teacher. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May.

Sharin Russell during her early years at the School as a 4th grade homeroom teacher. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May.

1993: Finding myself in fourth grade

On my first day of fourth grade, as the “new kid” at Brimmer and May, I remember how the sun’s warm and welcoming glow enveloped McCoy Hall. I fluttered between eager anticipation and high anxiety. Inside at the top stairs, I located my classroom nestled at the end of the corridor. A lively woman graced the doorway, her beaming smile greeting students; she sparkled in the light that flooded in from the windows behind her.

“Welcome to Brimmer and May,” said my homeroom teacher Sharin Russell, before showing me to my spot. “We’re going to have a great year, and we are so happy that you are here. From that moment, I felt reassured that I was seen and that I mattered—that I was exactly where I was meant to be.

Nearly three decades later, that feeling continues to burn brightly within me, serving as a constant reminder of the powerful impact a caring educator can have on a student’s life, even through a simple welcome. Under Mrs. Russell’s loving guidance, I anticipated weekly quizzes with excitement, found myself immersed through diligent research in the rich intricacies of Japanese culture, and embraced the intellectual challenge of labeling all 50 states on an unmarked map.

Long before global learning became an educational focus, Mrs. Russell had already embraced its core tenets. Without the Internet, she facilitated pen-pal exchanges to connect her students with counterparts from around the globe. In my young life, of all the people I had encountered up until that point, she held an unmatched ability to cultivate in me a profound appreciation for diversity in all its forms.

I reminded Sharin of as much when I spoke with her recently about her transformative impact on me, not just as a student but also as an educator. She still radiates the same captivating glow. She possesses a rare quality that makes students and colleagues feel completely at ease, as if they can confide in her without any concern of judgment or gossip (and they can).

David Cutler's 4th grade homeroom teachers, Brian Allieri and Sharin Russell, made him feel so welcome. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May.

David Cutler's 4th grade homeroom teachers, Brian Allieri and Sharin Russell, made him feel so welcome. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May.

2023: Maintaining an even keel

Sharin still radiates the same captivating glow I noted when I first saw her. She possesses a rare quality that makes students and colleagues feel completely at ease, as if they could confide in her without any concern of judgment or gossip (and they can).

Even with the passage of time and her transition in 2001 from a full-time classroom teacher to the Director of Annual Giving, she effortlessly shares an anecdote of me as her student, as if it had occurred just yesterday rather than three decades ago.

"I vividly remember when your mom would pick you up," Sharin excitedly tells me, when we catch up as my summer break starts. “I’d always have something to say, like, 'David did this great job, or he’s such a wonderful helper. Oh, he’s trying so hard.’ She would look at me and say, ‘Are you talking about my son, David? I don't know what you're doing, but when he's at home, he’s a very different person.’ And I said, ‘Well, I'm here to tell you, he's been amazing. I can only tell you that he works so hard. He's so polite and thoughtful.’”

Of course, my mom was correct: I wasn’t exactly the model child at home. Still, Sharin's ability to understand who I was as a fourth-grader remains unwavering even today, as does her understanding of me as I approach the age of 40. She effortlessly yet compassionately identifies something that I still grapple with to this day.

"Although I have to admit," Sharin says, "I distinctly recall talking with your mom about how our focus would always be on helping you understand that none of us can be perfect all the time."

I nod in agreement, as I share my own recollection of crying when I earned a B+ on one of her weekly quizzes, instead of my usual perfect score.

“That's when we focus on ‘how do I learn to be even-keeled about my emotions and get through it, and then say, okay, let's learn from this and move on,’” Sharin tells me. “But I think your passion for things is what makes you an incredible person.” I blush at her sincere words.

I’ve since learned to maintain a more “even keel” when dealing with setbacks, though I still grapple with anxiety, particularly concerning my health and the pursuit of perfection as an educator and father—impossible goals to attain. True to her nature, Sharin pinpoints a silver lining in how my own struggles empower me to empathize with students’ needs.

"No matter who we are, we seek recognition, aspire to be a guiding light, and yearn to feel valued,” she says, affirming my efforts to overhaul my 11th-grade US History class with the same intention. Next year, I aim to help students see themselves in the curriculum—not just through scholarly textbook authors, but also through diverse and engaging sources that emphasize their importance in our American story.

This is what sets Brimmer and May apart: compassionate educators who meet students where they are, cultivate their strengths, and support them in identifying and refining areas for growth. Thanks to Sharin, I would become an even more confident fifth-grader come the fall of 1994.

1994: Gaining confidence in fifth grade

I can vividly recall the first day of fifth grade.

Thomas Fuller—who would eventually become a colleague and go on to serve as the Lower School Head until his retirement in 2019—greeted students into the foyer. Although we had never met before, he invited me into McCoy Hall with an authoritative but soothing teacher’s voice, “Good morning, David Cutler. Welcome back to school.”

I later found out that Mr. Fuller had meticulously reviewed our yearbook headshots to familiarize himself with our faces. Once again, I felt valued and seen, putting me more at ease on the first day of my last year in Lower School.

I also found comfort in the consistency of still having Bill Jacob as my drama teacher. In fourth grade, he had taught me Spanish, and I cherished his clear, deep, and theatrical voice along with his Robin Williams persona that reflected his compassionate, larger-than-life personality.

As a fifth-grader, I learned from Mr. Jacob to take risks, to go big, and to be unafraid—no small feats given my small stature compared to my classmates, most of whom towered above me.

Likewise, my memories of my fifth-grade physical education teacher, Jeff Gates, remain warm and vivid. Not only was he the Athletic Director until his retirement in 2022, but he also became a beloved mentor. His emphasis on the importance of thoughtfulness made a deep impression on my 11-year-old self.

Clad in his signature polo t-shirt, athletic pants, and running shoes, Mr. Gates urged me to think about my actions before I threw, caught, dived, jumped, or ran. Faced with my minimal coordination, he displayed unwavering patience. He never allowed frustration to surface; instead, he calmly encouraged me to persist, learn from setbacks, and always give my best honest effort, no matter the outcome.

In spring 2022, at our 20th high school reunion, my close friend and classmate Thomas Byrne '02 echoed similar sentiments upon his induction into the Athletic Hall-of-Fame.

“I can’t think of a nicer man on the planet, who put up with a lot of shenanigans that my friends and I created when we were here in high school. He’s just very supportive of all of the teams, and he’s basically tireless. . . . I am really happy for him to be sailing off into retirement,” Tom said.

Revisiting Tom’s remarks a year after he offered them, I couldn't help but also think about how Mr. Gates still hasn't really left; he still cheers on the Gators at home and away games, and I enjoyed catching up with him during last winter’s exciting varsity basketball season.

Thomas Fuller welcoming a student to the first day of classes in the early 2000s.

Thomas Fuller welcoming a student to the first day of classes in the early 2000s.

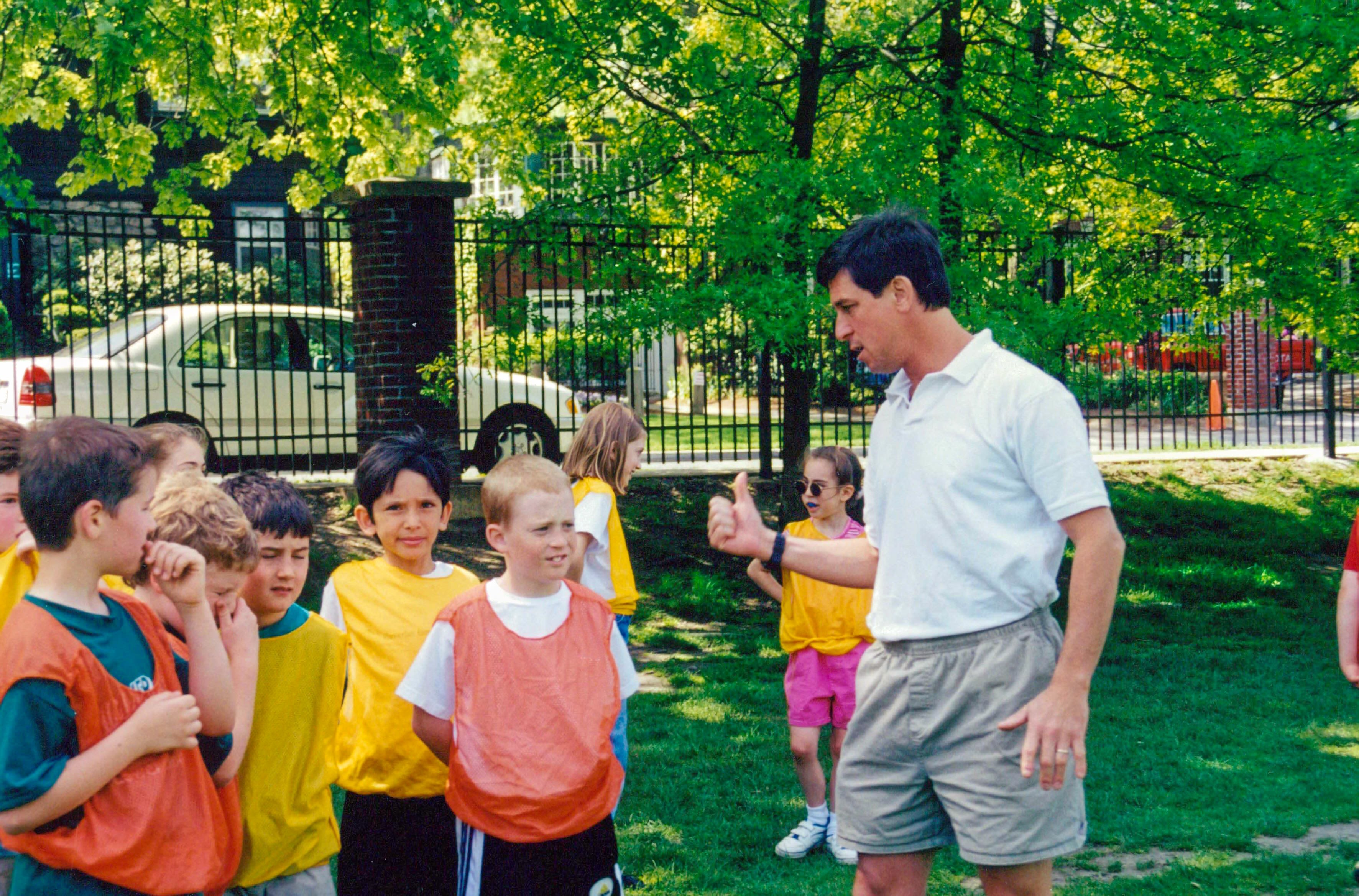

Jeff gates teaches a physical education class in the late 1990s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Jeff gates teaches a physical education class in the late 1990s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

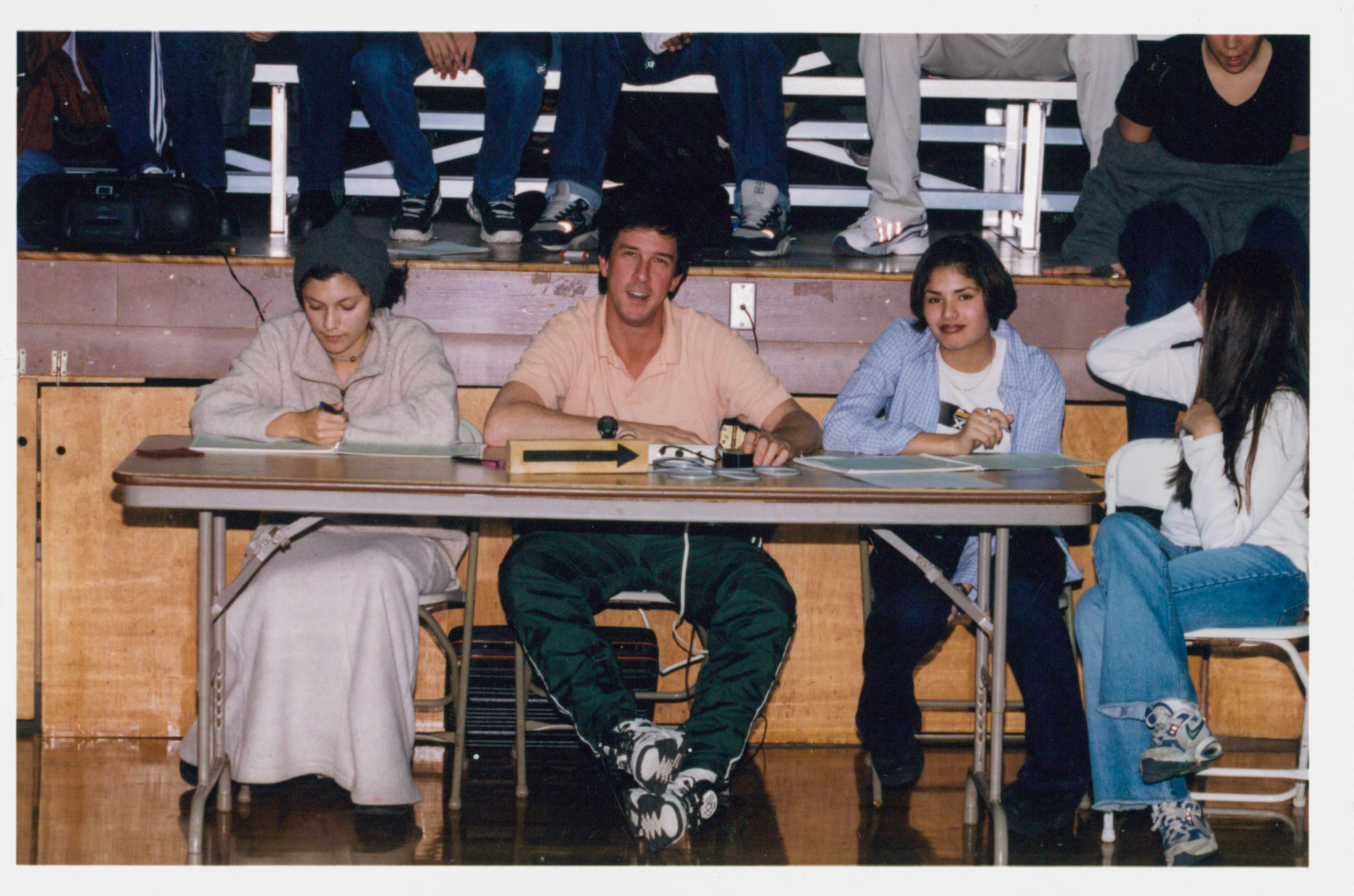

Jeff Gates keep score during a home basketball game in the early 1990s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Jeff Gates keep score during a home basketball game in the early 1990s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

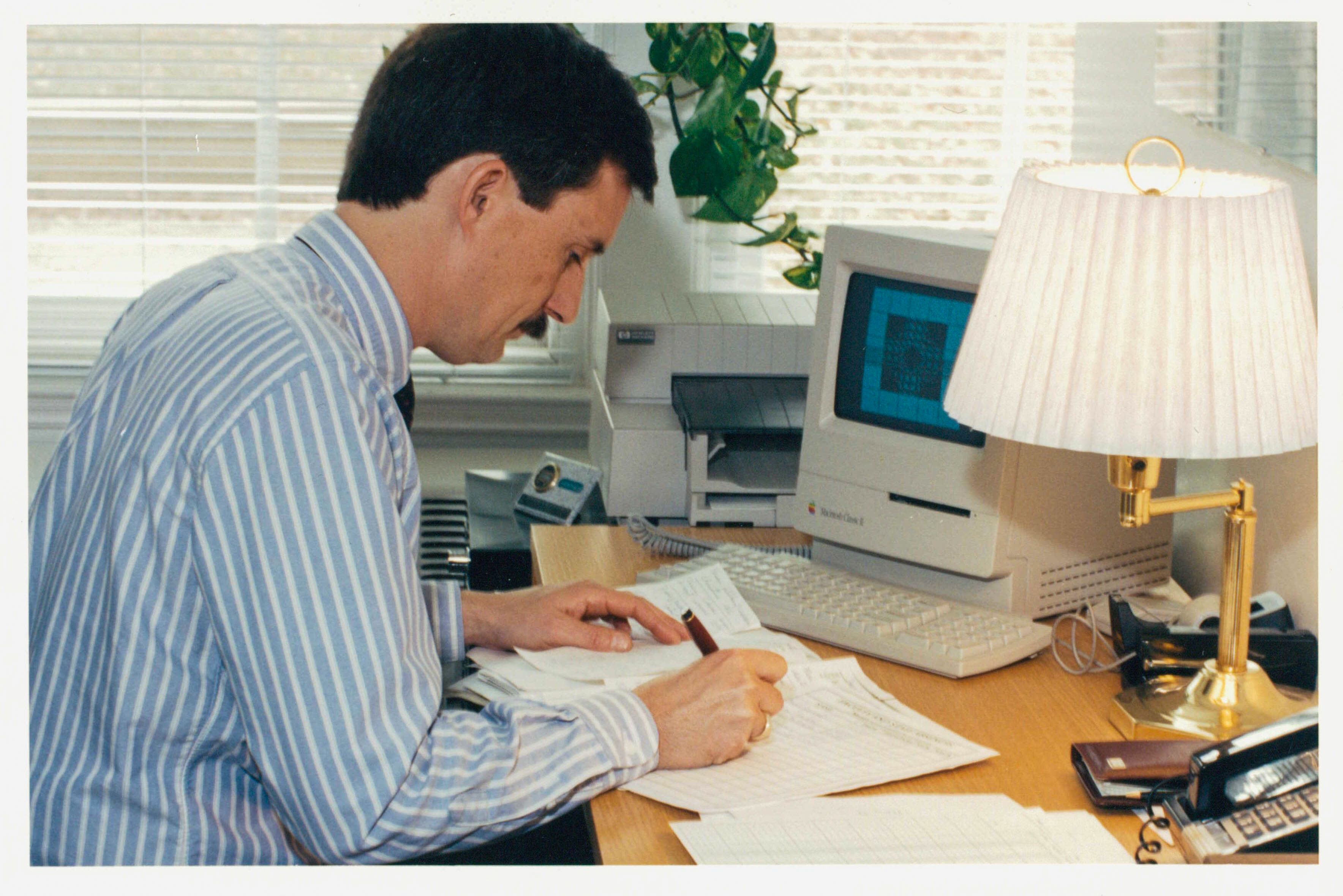

Thomas Fuller working at his desk in the early 1990s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Thomas Fuller working at his desk in the early 1990s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

2023: Expressing care for my students

In the same way, even in retirement, Mr. Fuller has yet to miss a senior graduation, underlining the special character he and Mr. Gates, like so many other educators here, past and present, embody.

When I reconnect with Thomas Fuller over the summer, four years into retirement he still very much looks the part of an experienced, lifelong educator.

I share with Thomas that I aspire to emulate his dedication in my own teaching career, and into retirement. When I ask him why he keeps returning for graduation, he offers a touching and logical explanation: “Teaching can be likened to working on a Ford assembly line. Elementary school represents the beginning of the assembly line, where we lay out the fundamental parts for the car and develop the frame. As students progress through middle and upper school, we add the intricate details—the plush upholstery, the radio, speedometer, and other enhancements. Graduation signifies the end of this educational assembly line. Wouldn't you want to see the finished product? To me, that's the essence of it all.”

Thomas embodies the quintessential Brimmer and May educator, going beyond considering our role as just a job. It is a vocation that deeply resonates, fostering a sustained commitment to the growth and development of students, whom we care for wholeheartedly.

“The child needs to feel comfortable with whoever it is, and the only way you can do that is by knowing one another,” Thomas says, as I think to myself that it’s an integral ingredient in making our community so special.

Continuing a tradition that predates my time as an Upper School student here, before the start of each academic year, my colleagues and I establish connections with our students at Camp Wingate-Kirkland in Yarmouth Port, Massachusetts. There, we spend an overnight (or two for seniors) interacting with and valuing one another as unique individuals.

Inspired by Thomas, I make it my goal at camp to learn the names of all my new students before returning home. Last fall, I asked students to submit video recordings of their names and preferred pronouns to help me get them right.

When reflecting on precision with names, my thoughts inevitably turn to Bill Jacob, who every year articulates our graduates’ names as they step onto the stage to receive their diplomas. In high school, I delved deeper into vocal expression in Bill's “Public Speaking” course, the most pragmatically beneficial elective I've ever taken. I convey disappointment that the course was discontinued years ago. To my delight, he responds, “I've been tapped to help bring it back in some capacity.”

Bill’s enthusiasm for teaching remains as strong as ever, even as he has moved on to the role of Creative Arts Department Chair, with many of his teaching responsibilities now in the Upper School. His commitment to his craft and students is truly phenomenal, and watching one of his productions, one should think twice before muttering “it’s just a student show, where good is good enough.”

The proof is in the pudding— anyone who has seen one of Bill’s theatrical productions can attest to the exceptional quality and dedication that goes into each performance.

As I support my students in the development and continued success of The Gator, Brimmer’s highly-regarded online newspaper, I find motivation in Bill’s approach.

Following his example, I insist on the highest standards for my journalism students. Accepting mediocrity as the norm is unacceptable; I do my best to encourage them repeatedly to strive for excellence. No matter the outcome, I hope my encouragement conveys the depth of my belief in their ability to excel. The Gator's ongoing success in winning the nation’s most prestigious scholastic awards is a testament to the wisdom of learning from Bill's example; I’m still learning from him.

When I ask Bill what it’s like having me as a colleague, his tender comedic side shines through: “When I was a kid growing up, I would read Archie Comics, and I remember thinking about these poor people who always have Miss Grundy—like every year they have Grundy as their teacher. It just occurred to me that I am your Miss Grundy. I'm like the teacher who never goes away.”

I let him know that I wouldn't want it any other way. I feel similarly about Paul Murray, who served as my eighth-grade humanities teacher.

1994: Maturing in 8th grade

Prior to the start of eighth grade, the Middle School embarked on a bonding trip to Camp Cedar in Casco, Maine.

My classmates and I bunked with Mr. Murray—who would later become the Upper School Dean of Students and another close colleague—a new teacher who had just joined Brimmer. His vast knowledge of sports, theater, history, and popular culture quickly endeared him to us. Later that year, he competed in “Jeopardy” and triumphed during his first appearance, cementing his popularity. I still can't help but smile at a framed photo of him posing with Alex Trebek in his office.

Two years earlier, I had attended Cedar, a sleepaway sports camp, eager to spend time with my brother, a future college lacrosse athlete. However, my lack of athletic skills left me feeling out of place.

Upon my return with Brimmer, my anxiety surged as my former counselors officiated a round-robin soccer tournament, with the entire Middle School divided into several teams. Despite my limited athletic abilities, I was resolute in showcasing any progress I had made. Recognizing my determination, Mr. Murray provided the support I needed, enabling me to excel briefly as a goalkeeper.

“You've got this, David,” Mr Murray cheered me on from the sidelines. “Don't be afraid to move out of the box and get the ball. Let your teammates know what you need.”

My team reached the final match, culminating in a tense shootout. The pressure weighed on me, and I couldn’t help but wonder when my luck would finally give way.

“Just choose a goalpost to protect,” Mr. Murray yelled. “Take a chance and that's the best that anyone can do.”

Regardless of the outcome (I blew it), for the first time in my life, I experienced a newfound confidence on the athletic field. However, I still had to work on my confidence in the classroom.

During the spring, Mr. Murray stepped in once more to assist me in the "Big Dig," a once popular tradition which divided the eighth-graders into two groups to conceive unique cultures, each rich with art and detailed backstories. Eventually, Mr. Murray broke apart the “artifacts” and buried them outside near May Hall. Subsequently, our teams excavated the site of the other group, which we were told had been undisturbed for a thousand years. We worked to assemble the unearthed artifacts, striving to decode the narratives of these simulated ancient civilizations.

I worked hard to reassemble several paintings, which had seemingly been torn from their frames, but I remained unsure about whether I was proceeding correctly.

“Am I on the right track?” I repeatedly asked Mr. Murray, who remained patient and steadfast with me. “Can you give me a hint? I want to be sure I am doing this correctly. Am I doing this correctly?”

Understandably, he refrained from providing any guidance, which would have defeated the purpose of the exercise. But he always listened to me, and he made me feel seen.

“David, just do the best you can,” he said. “If it’s not perfect, that’s okay. Just keep moving forward.t

Paul Murray performs during a coffee house in 1998. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Paul Murray performs during a coffee house in 1998. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Paul Murray coaching students at Camp Cedar during the early 1990s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Paul Murray coaching students at Camp Cedar during the early 1990s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Ted Barker-Hook and Paul Murray coaching softball in the early 2002s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May.

Ted Barker-Hook and Paul Murray coaching softball in the early 2002s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May.

David Cutler, front row wearing glasses and holding a soccer ball, posses with his 8th grade soccer team. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

David Cutler, front row wearing glasses and holding a soccer ball, posses with his 8th grade soccer team. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

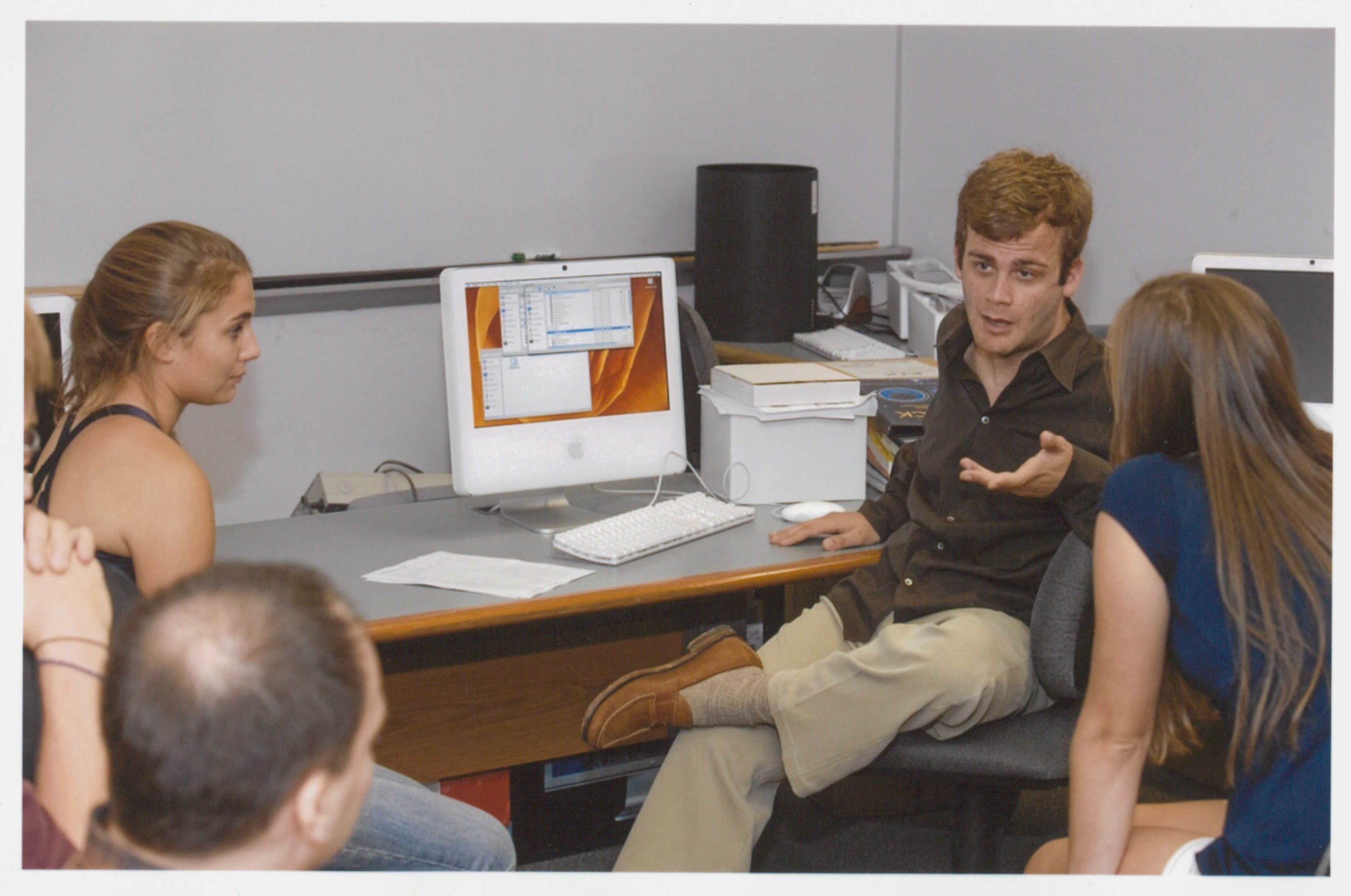

David Cutler '02 teaching yearbook during his first stint as a teacher at Brimmer and May, back in 2007.

David Cutler '02 teaching yearbook during his first stint as a teacher at Brimmer and May, back in 2007.

David Cutler's 5th grade class shot. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

David Cutler's 5th grade class shot. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

In 2017, David Cutler speaks about The Gator and student voice in front of the Board of Visitors.

In 2017, David Cutler speaks about The Gator and student voice in front of the Board of Visitors.

2023: Listening to my students

Paul still frequently reminds me that the path to growth and progress is rarely, if ever, a straight one. This June, we reminisce about my time as his student, and I seize the opportunity to express my overdue gratitude for his patience and faith in me—both as a student and now as a peer.

He appreciates the sentiment, but he assures me that no apology is necessary.

“At Camp Cedar with that story, I was an ad-hoc soccer coach for you at that moment because that's what you needed,” Paul tells me, correctly observing that being anxious is simply a part of who some people are, and that it’s our role as educators to meet students where they are—and to really listen with empathy. “Just the simple act of listening lets kids and adults know that you care and that they're being heard. You know, listening is the single most ethical act one human can provide for another human. I’m glad to hear that you felt I could offer that for you when you needed it.”

Even after all these years, Paul continues to support me.

I frequent his office to discuss teaching methods and my handling (or mishandling) of certain situations. I often ponder what I could have done differently, and Paul reminds me about the “anxiety monster” perched on my shoulder: "Do you constantly feed it all the time? Or do you say, 'Okay, monster, you're going to stay over here for now because I have other things to do'?”

Paul’s support and guidance have been crucial in helping me navigate my students’ needs, as our nation grapples with a surge in adolescent anxiety. I periodically remind my students that though my main role is as their teacher, I'm also here to listen to anything that is weighing on their minds. By doing so, I think I have fostered a deeper level of trust with students, enabling me to be a more effective teacher.

Thanks to Paul, I also try to demonstrate to my students that I am human and prone to making mistakes. Last year, I made several errors by posting incorrect due dates, which I acknowledged and attempted to correct. I also neglected to whiteout a student's name before presenting her exceptional in-class essay as an exemplar. By acknowledging my own flaws, I convey to Paul that I hope to inspire my students to feel at ease learning from and confiding in me.

“It's so important as an educator to show vulnerability,” Paul tells me. “That also builds trust and helps students identify with you as a person.”

Throughout high school, I continued to benefit from building trust with a remarkable team of educators, who for the past 10 years, I have proudly come to call my colleagues. Together, they helped me find myself and reach my potential.

2000-2002: Finding myself in Upper School

For the first two years of high school, my parents recommended that I transfer from Brimmer to another nearby independent school. They valued Brimmer, but they thought I would benefit socially from a larger circle of friends. To this day, conveying the enormity of this error remains challenging, as I felt like a social outcast and experienced greater anxiety and depression as a consequence. It's difficult to engage in academic learning when one feels emotionally wrecked.

I'm unsure why I lingered for two years before transferring back to Brimmer. Perhaps it stemmed from a trait my teachers often noticed in me: a dogged inclination to see things through to their conclusion, which I saw as doing it “right.” It’s funny how the mind sometimes blocks out bad memories and experiences, for as much as I lovingly recall my final two years of high school back at Brimmer, I remember almost nothing of my first two years at that other school.

I returned to Brimmer in the fall of 1999, already having taken American History, a course I now teach and which remains an 11th-grade requirement. Fortunately, I had little choice but to enroll in Ted Barker-Hook's Modern United States History class, which, though not officially labeled as an AP course, held a reputation for rigor.

As an emotionally fragile 16-year-old, I couldn't have found myself in a more fortunate position. Being the only junior in the class, I was supported by my 12th-grade peers in every way imaginable. They treated me like a younger sibling, and during the annual Ring Ceremony, they all took to the stage to talk about me and present my gift.

“We care about and love this awesome junior, who is so special and is going to do great things next year,” I recall Reed Allmendinger ‘01 saying to the packed audience, as I came up onto the stage to give him and my other peers hugs. It felt amazing to feel not simply accepted, but also embraced.

I felt that same support from Mr. Barker-Book, who, rain or shine, always sported a leather bomber jacket with tan, khaki pants. As a socially awkward young person who lacked confidence in himself, I valued Mr. Barker-Hook as a teacher and mentor. Nobody taught me more about clear and concise writing, or how to think analytically rather than skimming the surface. In his office, then located on the second floor of May HalI, he spent countless extra hours teaching me to revise my prose for clarity and concision.

After graduation, I fondly recall my father approaching Mr. Barker-Hook, jokingly telling him, “So, you’re the wise guy who made my son stay up late every night writing papers for your courses.”

Not aware of my father’s humor (in all fairness, he can be difficult to read), Mr. Barker-Hook looked taken aback.

“Me? I’m the wise guy,” Mr. Barker-Hook responded. “When I ask for five pages, your son submits 15-pages, sometimes more. I’m the guy who has to stay up late to grade after my family is asleep. It’s more like ‘poor me.’”

Afterward, we all laughed and hugged.

In 12th grade, I also had Mr. Barker-Hook for Modern World History, where he held me to higher standards than my 10th-grade peers (in 2001, the School didn't offer nearly as many classes as it does today, leaving me with few other history courses to choose from).

By the end of 12th grade, I had come a long way, as Mr. Barker-Hook attested in his year-end comment about me: “All year I tried to push David beyond my expectations for his sophomore classmates, and he responded with energy and enthusiasm. Having had the chance to teach him for two years, I have seen his writing improve dramatically; both the sophistication of his analysis and the fluidity of his presentation have come a very long way since September 2001.”

Like Mr. Barker-Hook, my Algebra II and Precalculus teacher Nancy Bradley appreciated my unwavering determination. I didn’t progress as fast in math as I did in history and writing, but that didn't stop me from seeking her out for extra help at every opportunity.

“As the material grew more challenging, David put in more time,” Mrs. Bradley wrote in her year-end 12th-grade comment about me. “I am impressed with the work that he has done over the past two years, and his dedication to doing his best at all times.”

I didn't always arrive at the correct answer, but I gained analytical clarity. I appreciated how Mrs. Bradley’s pushing to help me think logically also assisted me in my other subjects. In a very real sense, for as much as I struggled in it, math helped me become a better thinker—and thereby a more thoughtful person.

In biology, with Cecilia Pan as my teacher, I also felt that I was learning something beyond just the subject matter. By delving deeply into RNA, DNA, and the cellular cycle, I gained a greater appreciation for science. My health anxiety also diminished once I learned how my body protects itself against bacteria and viruses.

I adored learning about Charles Darwin and his groundbreaking work in evolutionary biology. She captivated my attention by teaching about the 1925 Scopes "Monkey Trial,” a historical legal case in which a teacher faced prosecution for violating Tennessee's ban on teaching human evolution in public schools.

For intellectual exploration, as an 11th-grader, I also felt privileged to be in Judith Guild's AP Literature class. I had never met anyone as well-read as she was or with such a profound grasp of the human condition. I fondly remember comparing and contrasting Charles Dickens’s Hard Times with Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South, two novels written by contemporaries and set during the peak of England’s Industrial Revolution.

I also remember being captivated by A Good Man Is Hard, a collection of stories by the celebrated Southern author Flannery O’Connor. Mrs. Guild's engaging discussions and thought-provoking inquiries about the themes within the literature, especially around the concepts of good, evil, and redemption, played an essential role in shaping my maturing understanding of morality.

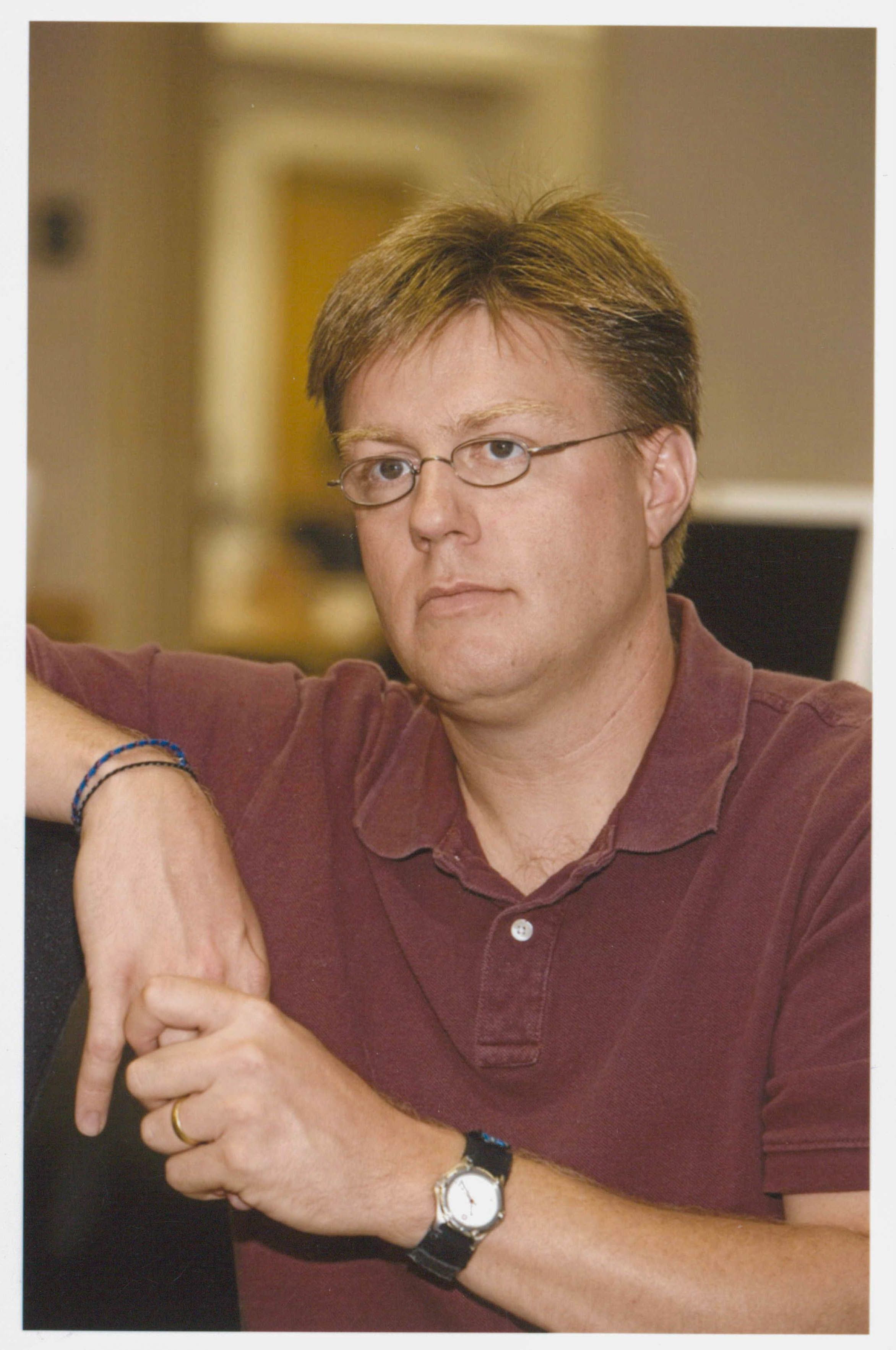

Ted Barker-Hook between classes in 2007. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Ted Barker-Hook between classes in 2007. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

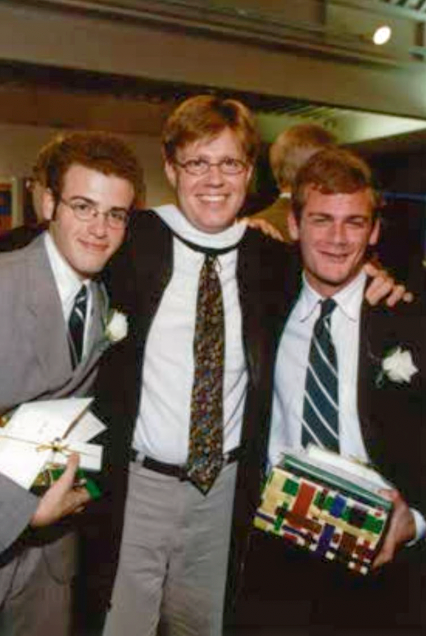

Ted. Barker-Hook poses with David Kazis and David Cutler and their 2002 graduation. Photo by David Barron.

Ted. Barker-Hook poses with David Kazis and David Cutler and their 2002 graduation. Photo by David Barron.

Nancy Bradley teaching a student in the early 1990s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Nancy Bradley teaching a student in the early 1990s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Nancy Bradley teaching a math class in the late 1990s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Nancy Bradley teaching a math class in the late 1990s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Cecelia Pan prepping for a sciecne class in the early 1990s. Photo Courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Cecelia Pan prepping for a sciecne class in the early 1990s. Photo Courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

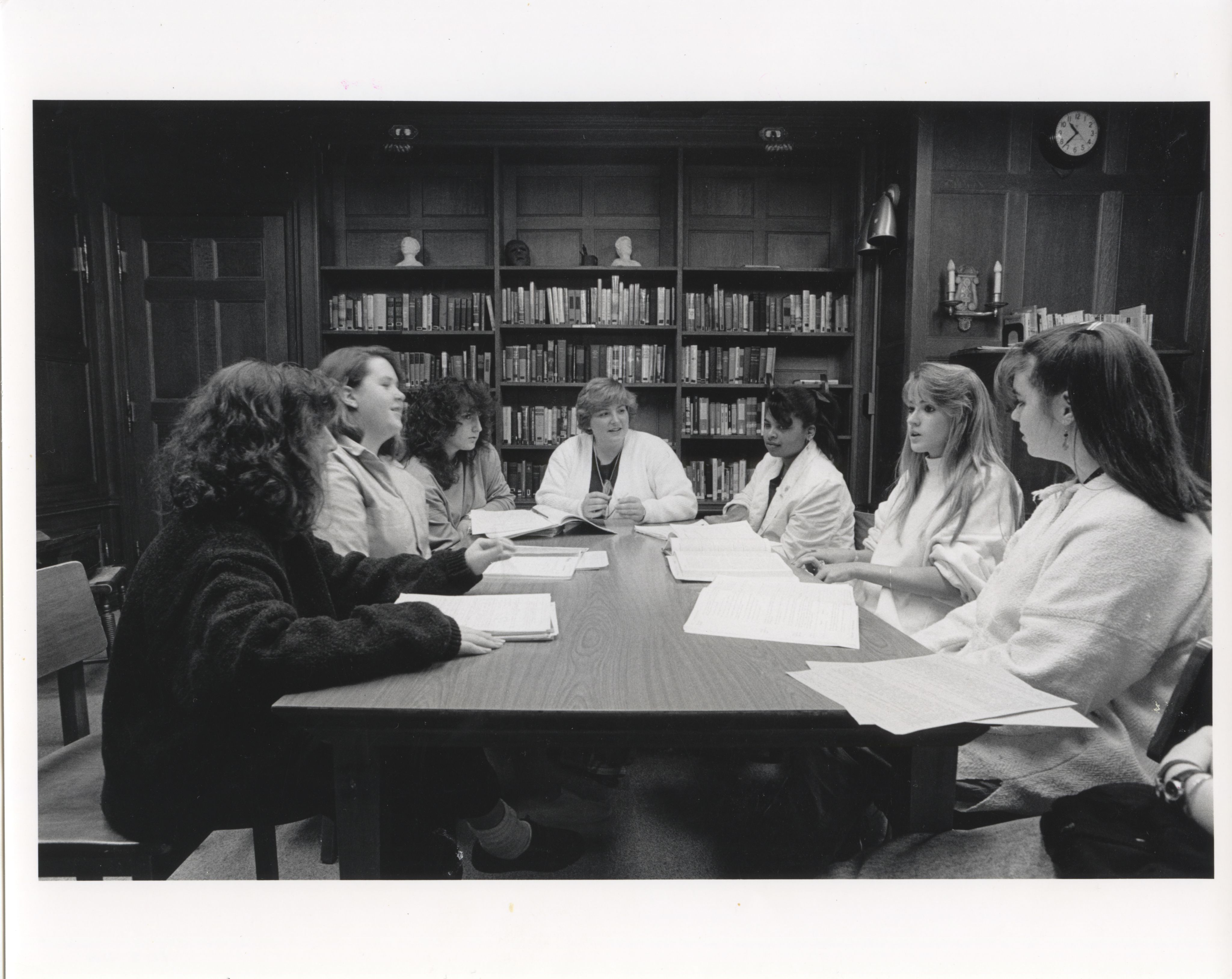

Judith Guild teaches a 9th grade seminar class in the early 1990s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Judith Guild teaches a 9th grade seminar class in the early 1990s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

2023: Helping my students thrive

Upon her return from break a few weeks ago, I reconnect with Judith, who now serves as the head of the school. I tell her that, as a teacher myself, I am continually working to guide my students in discovering their own moral compasses, just as she had done for me during high school.

I encourage my history students to embrace discomfort, historical empathy, and how a better understanding of the past can inform their own sense of right and wrong.

I feel further affirmed in my approach when Judith tells me that good teaching “comes down to helping students develop a passion for lifelong learning, which we hope also guides them in developing a high-quality moral compass.”

Judith says that I still possess the same moral compass she first saw in me as a student: “You aren't willing to just go the easy route and say, ‘oh no big deal,’ if you see that something is not right. You share your concern with others, and you do it respectfully.”

Respectfully, Judith gives me too much credit for cultivating those qualities without reinforcement from educators like herself.

In this vein, when I ask if Judith remembers me as an anxious high school student, she pushes back: “You were earnest and eager to do what was right. That didn't allow you to look me in the eye and say, ‘here's my work’ when you really hadn’t done your work. I saw that thoroughness as proof; you wanted to prove that you really did your work, even if I asked for one page and you submitted five.”

Judith says that as an educator, she knows I strive to impart an equally strong sense of integrity to my students. With advances in Artificial Intelligence, it is easier than ever for them to cut corners and be dishonest. I want students to do the right thing, even though it may not always be the easiest path to take.

Judith says that my striving to always do the right thing, even if I sometimes fall short, is why I have continued to succeed in advising The Gator.

“You want to remain true to journalistic values and principles, but you also want to make sure you don't harm students. I count on that, and I think you were the same student when I taught you. You wanted to do the right thing.”

When I recently reconnected with Nancy Bradley, she echoed the observation above from her experience as my math teacher.

“I couldn’t give you a problem you wouldn’t be determined to do correctly,” Nancy tells me. “I think that's something you had, innately. You weren't going to give up, even if I said, ‘David put your pencil down.’”

Math was my weakest subject in high school, but I tell Nancy that I could not have asked for a better, more patient and effective teacher. Often, it’s the humanities and creative arts teachers who receive praise for fostering a student’s voice and character, but in my case, and I suspect for many others as well, Nancy deserves equal credit in this regard. Now as an educator, I recall her influence whenever I assist students grappling with a skill or concept; I strive to inspire them to articulate their thoughts as well, which fortifies character and self-initiative.

"You've always excelled at making your voice heard, and I loved it; I still do," Nancy says.

Reflecting on this trait during another frank discussion with Ted Barker-Hook, we recall the countless hours he devoted to refining my expression. I feel choked up, expressing to him that I would not be where I am today without his steadfast belief in my ability to improve.

“I’ve found that one of the hardest things about teaching and coaching is knowing how hard you can push individual students—knowing when you need to back off and knowing when you need to throw some extra love their way, even though more work needs to be done,” Ted says. “And I think when I taught you—and I was still a young teacher then—I was trying to walk that line with you because you had so much promise and you were so clearly bright.”

I'm continually learning from Ted about how to motivate students without inadvertently causing burnout. Following his advice, I've shifted away from the traditional practice of assigning zeros to missing assignments, which disproportionately hinders one’s ability to recover academically. Starting last fall, I incorporated his method into my grading system, where I count uncompleted work as half-credit. This encourages students to remain persistent, countering the belief that their efforts are futile when they encounter setbacks.

Envision my joy over the past decade as I've had the privilege of teaching adjacent to Ted's classroom. I feel a soothing nostalgia whenever his deep, resonant voice permeates our shared wall.

Our proximity also allows us to confer about best practices, and every week I ask Ted for some sort of advice; he has played a major role in helping me to think about overhauling my US History class.

When I was in high school, Ted sparked my deep-rooted passion for history and writing. I confess to him that without his mentorship, I wouldn't have flourished as a history major at Brandeis University, risen to the position of news editor for my college paper, contributed to major media outlets, or felt the calling to mirror his career as a history teacher. I believe this is the highest compliment an educator can receive, and it’s one that Ted entirely deserves.

Judith Guild arrives to work in the late 1980s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Judith Guild arrives to work in the late 1980s. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Judith Guild attends Homecoming in 2006. Photo courtesy of. Brimmer and May School.

Judith Guild attends Homecoming in 2006. Photo courtesy of. Brimmer and May School.

Nancy Bradely at Interlocken, about to tackle the high-ropes course in 1999. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Nancy Bradely at Interlocken, about to tackle the high-ropes course in 1999. Photo courtesy of Brimmer and May School.

Ted Barkler-Hook coahses the 2023 Varsity Boys Cross Country Team. Photo by David Cutler.

Ted Barkler-Hook coahses the 2023 Varsity Boys Cross Country Team. Photo by David Cutler.

It’s the people that matter

Our School is blessed with excellent facilities that provide an environment conducive to learning. However, all too often, I feel that our community is judged based on its smaller campus and lower enrollment, which can lead to misconceptions about the real sources of our institution’s quality.

What isn't immediately apparent—but is of far greater importance—is the caliber of the educators at our school. Their commitment to nurturing young minds, their expertise in their respective fields, and their passion for teaching are the cornerstones of our educational approach. These intangibles have a profound impact on student outcomes, and they make our School a unique place of learning, regardless of our physical footprint.

Numerous faculty and staff members—not just Sharon, Bill, Thomas, Jeff, Paul, Cecilia, Judith, and Ted—have dedicated, and continue to devote, their entire professional lives here. This fosters an unparalleled continuity and depth of knowledge, contributing to each student’s journey of learning.

In my view, there is no finer educational institution than Brimmer and May. I hope my own journey here, from being a student to becoming an educator, testifies to that conviction.

David Cutler poses in his classroom. Photo by David Degner.

David Cutler poses in his classroom. Photo by David Degner.