Saying the Right Words: My Journey Through Stuttering

Andrew Flint '26 reflects on growing up with a speech disorder, sharing his story to inspire and educate others.

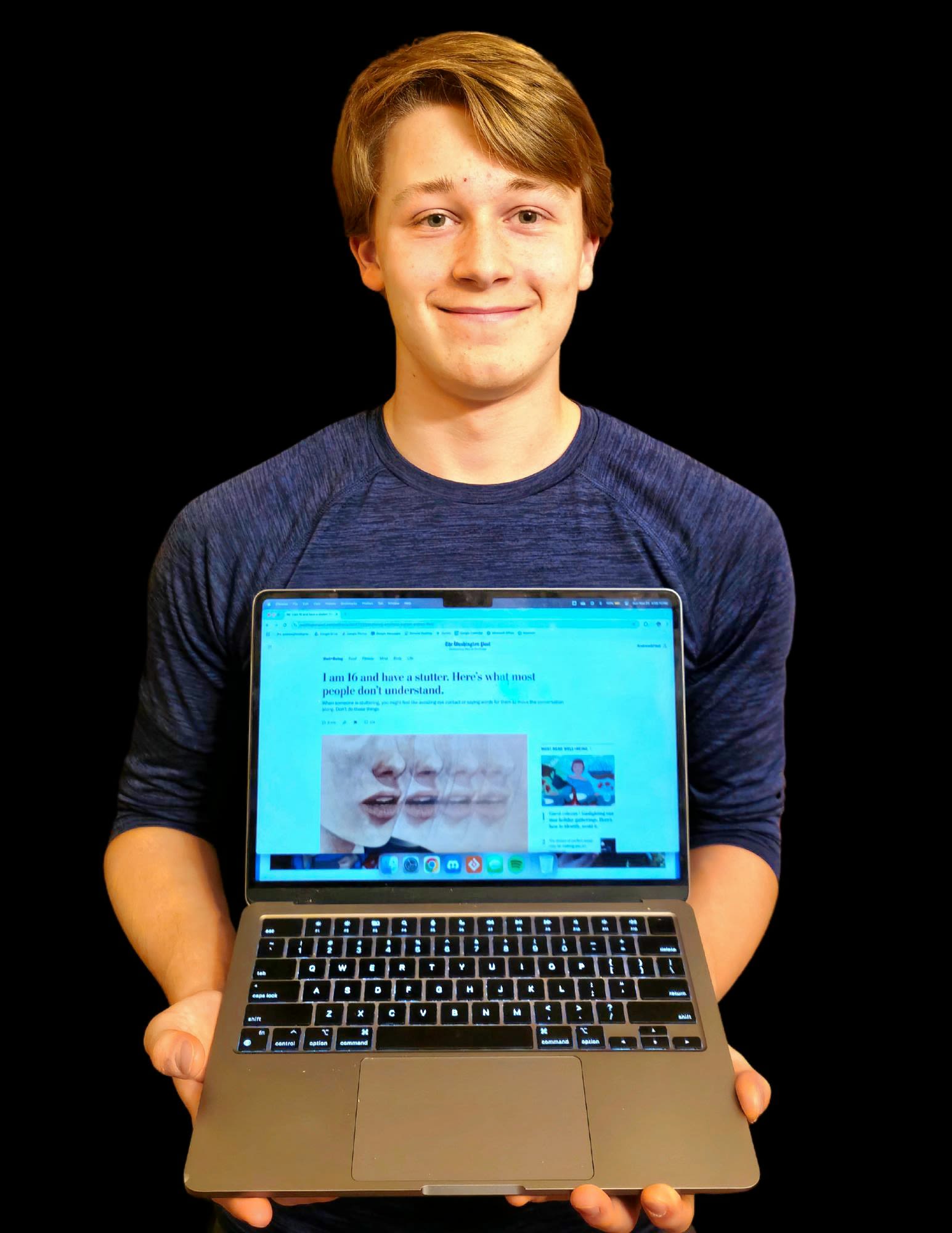

Andrew Flint poses with a copy of his article, which appeared in The Washington Post. Photo by Edward Flint.

Andrew Flint poses with a copy of his article, which appeared in The Washington Post. Photo by Edward Flint.

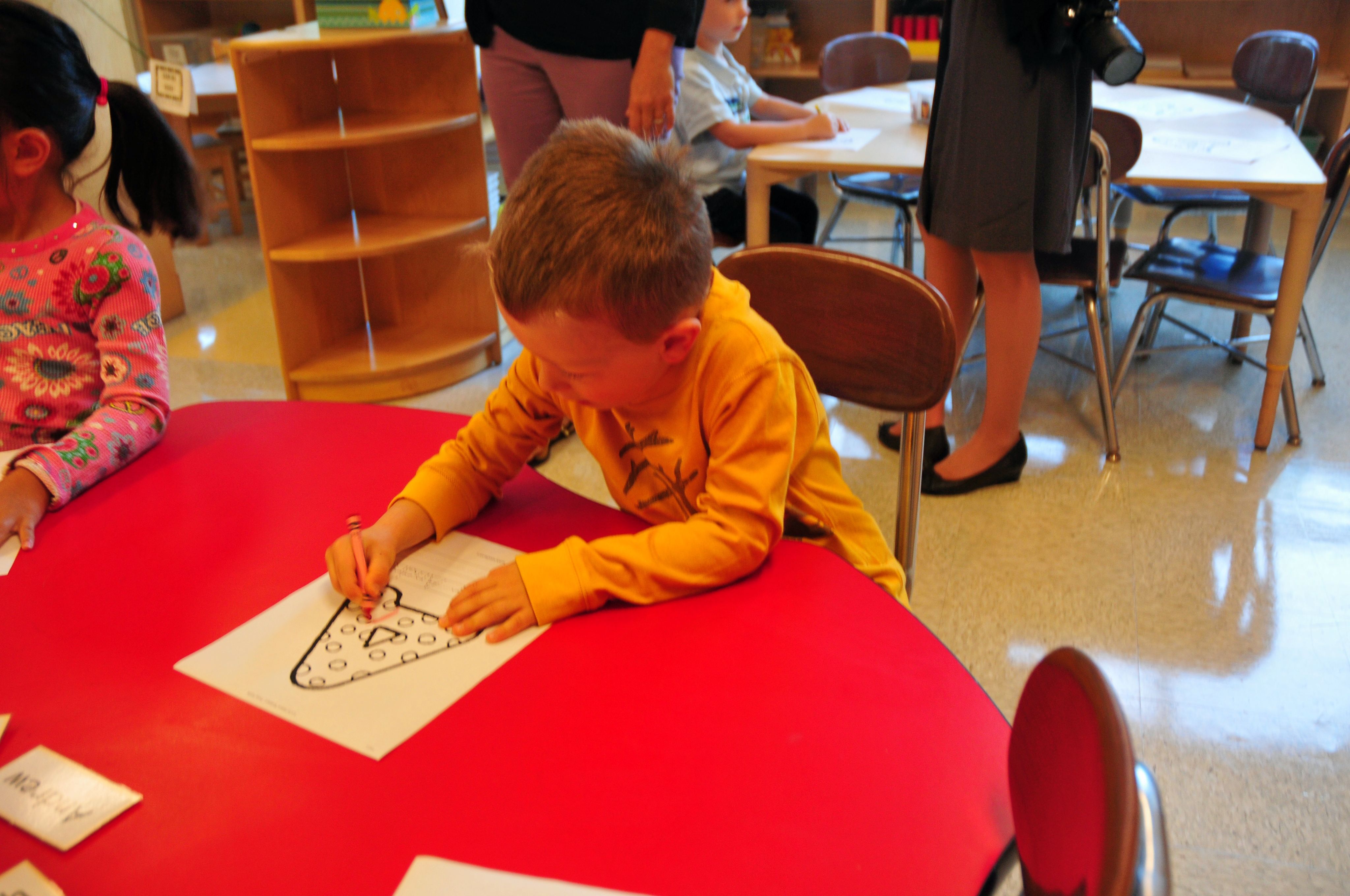

Andrew Flint '25 learns his letters in Kindergarten. Photo courtesy of the Flint family.

Andrew Flint '25 learns his letters in Kindergarten. Photo courtesy of the Flint family.

A young Andrew Flint listens to his teacher during morning meeting. Photo courtesy of the Flint family.

A young Andrew Flint listens to his teacher during morning meeting. Photo courtesy of the Flint family.

Andrew Flint takes photos in New Hampshire during a family trip. Photo courtesy of the Flint family.

Andrew Flint takes photos in New Hampshire during a family trip. Photo courtesy of the Flint family.

Andrew Flint goes skiing in third grade. Photo courtesy of the Flint family.

Andrew Flint goes skiing in third grade. Photo courtesy of the Flint family.

Editor’s Note: This story first appeared in The Washington Post on Saturday, Nov. 23, under the headline, "I am 16 and have a stutter. Here’s what most people don’t understand." A more in-depth version is republished here with permission from Andrew Flint and The Washington Post.

Stuttering is not what you think it is. Stuttering is not just getting stuck on words. It’s not just having a hard time saying a sentence. There is a deeper, hidden aspect to stuttering to which many people remain oblivious.

Stuttering is like an iceberg. The top part of the iceberg, the one sticking out of the water, that’s what everyone sees. But the tip is not the whole picture. What they don’t see are the turbulent emotions I feel while stuttering.

Stuttering, also known as Childhood Onset Fluency Disorder, is a speech disorder that affects about one percent of Americans. Stutterers know what they want to say, but they have a hard time saying it. There are three types of stutters: blocks, repetitions, and prolongations.

When a block occurs, the stutterer’s mouth and voice are stuck. Sometimes it feels like they can’t breathe as well. To make it worse, the harder the stutterer tries to push through a block, the more stuck they become.

The second type of stutters are repetitions. This is where a stutterer repeats a sound multiple times. For example, if they’re trying to say paper, they might say p-p-p-paper. Prolongations are like repetitions but involve prolonging the sound.

For example, if a stutterer is trying to say school, they might say sssschool, prolonging the initial s sound in school.

The exact cause of stuttering is unknown, but most researchers agree that there is a neurological and possibly genetic component to it. In my family, there are three stutterers: me, my dad, and my maternal aunt. There is no cure to stuttering, but speech therapy can mitigate its effects.

There have been numerous research studies showing that the brains of individuals who stutter have atypical structures. Specifically, the speech production centers in their brains function differently, resulting in certain limitations that can affect speech fluency.

However, these limitations can be combated with careful attention to conversation. When someone is stuttering, you may want to avoid eye contact or say what they are saying. The best thing to do is to maintain eye contact and let them speak in their own time.

It may be tempting to move the conversation along by finishing their sentences, but doing so will only remind the stutterer that they are doing something abnormal and making the other person impatient.

Andrew's parents, Dr. Christine Greco and Dr. Alan Flint, share their thoughts about his essay in The Washington Post and express how proud they are of their son.

Andrew's parents, Dr. Christine Greco and Dr. Alan Flint, share their thoughts about his essay in The Washington Post and express how proud they are of their son.

The best way to really understand what it means to stutter is to give you an inside glimpse at my life as a stutterer.

I am standing at the front of an 8th grade classroom full of people I have known almost my entire life. They know I stutter, and I know that they know I stutter. That does not make what I am about to do any easier.

In history class, we have been learning about the Supreme Court. I am now presenting the final part of what I have learned this year. I am in a debate. The facts are simple and I am confident I know them, but I do not feel calm.

Chloe Rose Scolnick '25 discusses with Andrew Flint '26 how he has approached stuttering, and what advice he has for others with the same speech difficulty.

This is because the facts cannot help me here. It is my turn to ask questions, and when I start speaking, and everyone quiets. Besides my voice, there is no sound in the room. The eyes of twenty people I know are on me, and I suddenly feel a tightness in my throat.

My heart starts to beat faster, and I feel my chest heating up. I say my question with great difficulty. I'm speaking very fast, but because I’m stuttering so much, the actual words are coming out painfully slowly.

The one or two-minute turn for me to ask questions feels like an eternity to me.

This eternity is not pretty either; it is filled with fear, anger, and guilt. As I am speaking, my mind is elsewhere. I should be focusing on what I am saying and trying to say it as clearly as I can, but I can’t.

Deep down, I know that my classmates are understanding of my stuttering, but this voice becomes buried by a louder one.

This one yells, “You should be ashamed of your stuttering,” and “No one stutters but you.”

Eventually, I'm able to piece together my argument and I sit back down. I should feel proud, but I don’t. Instead, all I feel is anger and guilt.

As the debate progresses, I am left wondering whether anyone else realizes how much courage it takes to do what I just did—to speak, to defy stuttering. But deep down, I know they don’t. They can’t, and that’s the worst part.

A year later, I entered a speech therapy program at Emerson College. My parents enrolled me in this program, and I relearned speaking through a difficult process that required patience and discipline. The program asked me to walk up to a stranger in a park and survey them about stuttering.

To a non-stutterer, this might seem a bit nerve-wracking, but doable. For me, however, it was terrifying.

Stuttering makes this usually easy task feel daunting and seemingly impossible. Nevertheless, I spot someone sitting on a bench and start walking over to them.

On the short walk over, my mind raced, imagining all of the bad things this stranger could say: They might me to go away, or say that they don’t want to talk to a stutterer, or even make fun of my stutter.

Andrew Flint plays Varsity Soccer this fall. Photo by David Barron.

Andrew Flint plays Varsity Soccer this fall. Photo by David Barron.

Andrew Flint (center) poses with his 2023-24 curling team. Photo by David Barron.

Andrew Flint (center) poses with his 2023-24 curling team. Photo by David Barron.

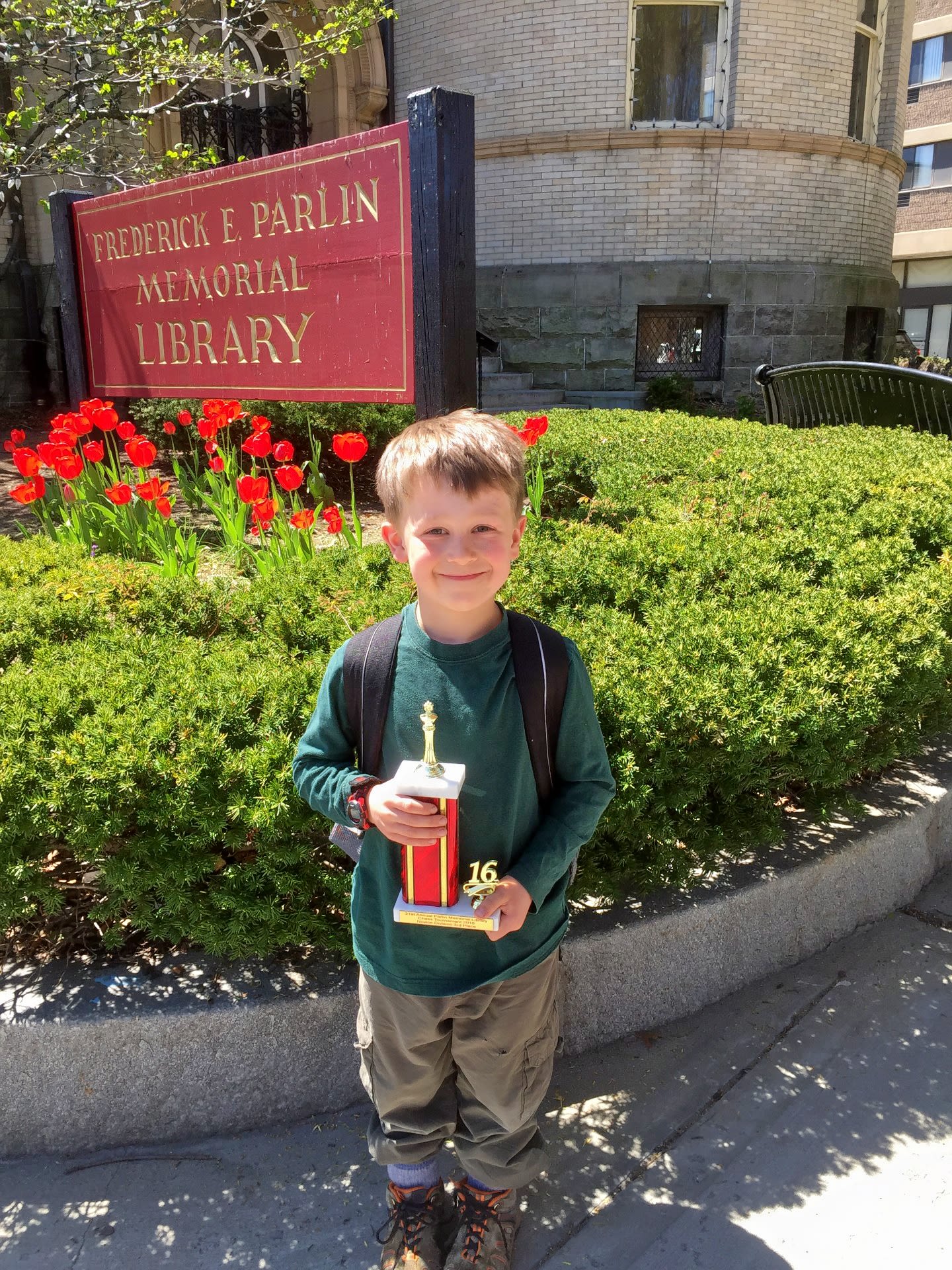

Andrew Flint wins a chess tournament in third grade. Photo courtesy of the Flint family.

Andrew Flint wins a chess tournament in third grade. Photo courtesy of the Flint family.

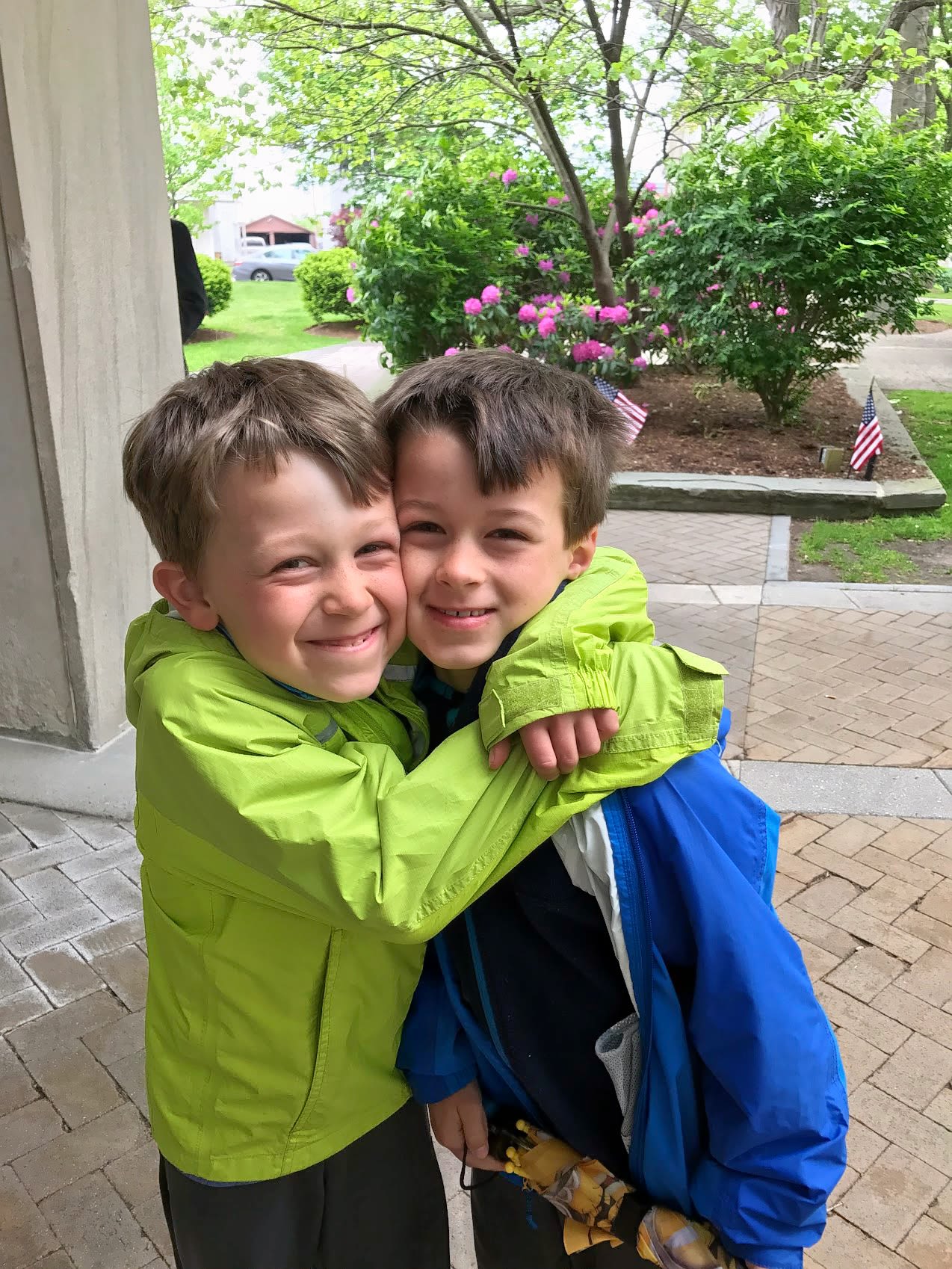

Andrew Flint (left) and his brother, Edward Flint (right) share a hug at age 7. Photo courtesy of Edward Flint.

Andrew Flint (left) and his brother, Edward Flint (right) share a hug at age 7. Photo courtesy of Edward Flint.

Andrew Flint plays in the Bookline Little League team. Photo courtesy of the Flint family.

Andrew Flint plays in the Bookline Little League team. Photo courtesy of the Flint family.

That is the miserable reality of stuttering; every interaction feels like I'm walking on eggshells. In my head, I always fear that the worst will happen, even though it never does.

I reach the person on the bench and say, “Hello, my name is Andrew Flint, and I stutter. I’ve been working on my speech in speech therapy. Can I ask you four questions about stuttering?”

To my relief, they told me that I could. I asked them what they thought caused stuttering, if they felt uncomfortable or embarrassed around a stutterer, if they knew anyone who stuttered, and what they thought someone should do to overcome their stutter.

In the end, this conversation went perfectly. It was not at all like what I envisioned and feared.

Nevertheless, I was apprehensive to surveying another person because I was still afraid.

Now, the fear that someone might not be as kind and understanding as the first person consumed my mind. See, the fear never fully disappears. It lingers, reminding me of that this struggle is inescapable.

Every day is either a good day or a bad day for my speech. On some days, I just stutter more than others. This is beyond my control, and it just happens.

One day in particular stands out to me. My history class involved frequent discussions, and I knew that I would stutter severely in discussion. When reading aloud, I always choose the shortest paragraph and am mindful of the initial sound.

The letter “s” is particularly challenging for me.

Eventually, I had an opportunity and I started to speak. Immediately, a knot tightened in my throat. My breathing quickened, and my heart beat faster and faster.

As I read the paragraph, I got stuck on words here and there, but I was eventually able to say them and continue speaking. That is, until I came across a word that I could not say fluently. Even before I started saying the word, I knew I would stutter on it. And I was right. I stuttered a lot; I stopped saying it then started saying it again, but that didn’t help.

After what felt like minutes - but was actually about twenty seconds - a classmate whispered the word I was stuck on to me. At that moment I had a realization: “Do they think I don’t know how to pronounce this word?”

That moment I realized something: People don’t know that much about stuttering, even classmates I’ve known for years. While I know they're just trying to help, these efforts often have the opposite effect.

Another year has passed. I am once again presenting in front of a large group of people. There are a few key differences this time, though. First, I met this group of people just four days prior. I barely know them.

On top of that, there are fifty of them. If this stressful situation isn’t stressful enough, all their parents are here. I am presenting medical cases, a topic I am not that familiar with.

Just as before, though, I have done my research. I know these four cases like the back of my hand. I know which slides I am presenting and which ones my group mates are doing, and I have practiced mine extensively.

I have prepared for every possible question. Nothing can possibly go wrong, I thought. Usually, that would be the case. For anyone else in my position, that would be the case. But I have a stutter. I can’t just know the content; I have to know how to say the content fluently.

Stuttering is another hurdle I have to complete to present. But I already took care of it. I already practiced my presentation.

I spent the previous afternoon saying it repeatedly in the mirror, then in front of my family.

Nothing can possibly go wrong.

My group is called to present. The teacher opens it on the big screen. One of the other group mates introduces all of us and presents the first slide.

He does a good job of presenting, and it is now the next person’s turn. He does an even better job, explaining the slide really well and giving so much additional information that even a baby could understand what he was talking about.

Then it was my turn. I look left at my group mates, who are all smiling and giving me encouraging looks. I look right at the screen with the slide I have to present. This slide is really simple information that doesn’t even need any explanation.

I literally just have to say what is on the slide. My heartbeat and breathing speed up. I take a deep breath to calm my nerves and start speaking. I open my mouth and freeze.

I can’t speak. Everything can possibly go wrong when stuttering is involved. My mouth is open, and to everyone else, it looks like I don’t know what to say. My group mates whisper the words, trying to help, but I can’t get them out.

I try harder and harder, but I forget one of the first things I learned about stuttering in the summer program: don’t push through it. Pushing never works. The best thing to do is to take a deep breath and release the tension. After what feels like five minutes to me—but only five seconds to everyone else—I remember this. I stop trying to speak, exhale, and start again. It works—I can make sounds again. While this technique successfully guided me out of a block, a type of stutter, it did not make me fluent.

As I said what was on the slide, I felt the eyes of all the strangers on me as I stuttered my way through the sentences, saying “um” as a filler word between each and every word. This continued throughout the presentation. It eventually got so bad that I wanted to run away. I have never had a presentation or a stutter so bad that I just wanted to leave as soon as possible, but in that moment I did. I did not run away. I kept on stuttering through the presentation, and everyone clapped at the end.

When we were walking back to our seats, I did not feel happy and proud that I just presented; I felt guilt, anger, fear, and almost every negative emotion you can think of. I felt all these emotions because all the years I have worked to rid myself of stuttering were apparently for nothing.

You’ve just read my stories of how devastating stuttering is, and you probably think, as a result, I try to distance myself from it. While I don’t want to stutter, the cruel fact is that I do. These experiences have helped me to learn that stuttering is a part of who I am. My friends and family have accepted me for who I am, regardless of my speech. They have helped me face my fear and accept who I am.

I have come a long way in my stuttering journey. I recently came across a recording from my speech therapy of me reading a passage. Two years ago, it took me two minutes and thirty-four seconds to read one hundred and twenty-nine words.

That is around 55 words-per-minute, which is a slow pace. The reason for this slow pace is because I was stuttering severely while saying it. When rereading the same passage two years later, it took me forty-three seconds to read the same amount of words.

That is around 188 words-per-minute, which is an average pace. When I read it recently, there was one major stutter, while the first recording was riddled with them. The second time I read the passage, I read three times faster. That is a major improvement that shows the growth in my stuttering.

I attribute this progress to speech therapy and the unwavering support of my friends and family. The Emerson speech program taught me effective techniques, gave me practice in using them and, most importantly, normalized stuttering. This improved my speech and reduced my stuttering.

The things I learned in the program would have gone to waste if it had not been for the support of my friends and family. I practiced the strategies with them while they patiently listened and encouraged me. This improved my speech and gave me confidence.

Now that I’ve told my story, I have one last message for you: If you stutter, know that you are not alone. Embrace your stutter. It has controlled your life forever, but that stops today. Do not let your stutter control you. Embrace who you are beyond your stuttering. Live your life.